The Lean Innovators Dilemma: What, When & How Much to Build

Aug 11, 2021

Two of my all time favorite nerd passions are baseball and human-centered innovation. I can spend all day studying saber-metrics and watching the standings in wild card races. Additionally, I love reading, writing and building the next generation of products, brands and consumer experiences.

And low and behold these two totally unrelated topics are connected by three simple letters– MVP. And while these letters mean completely different things in the different contexts, the dream of being a most valuable player and deploying the perfect minimum viable product is the shared ambition and obsession over these three letters. And as Major League Baseball is preparing for a Yankees vs White Sox "Field of Dreams" game later this week, I felt the itch to strength the connection between two of my great loves by talking about one of the most famous quotes from that movie and what I have started to refer to as the "lean innovator's dilemma."

The Lean Innovator's Dilemma

In one of the most iconic scenes of the film, Kevin Costner wanders into his corn field and hears a voice whisper a promise, "If you build it, he will come". The repeated voice and the vision of the "it" he needs to build is a picture of one of the most common myths in innovation. The false belief that great ideas come from some creative spark and vision. And the famous line, "If you build it, he will come" highlights a second great innovation myth– that because you love the idea, the world will inherently love it as well and all you have to do is meticulously build it and wait for the people to start flocking to what you have made.

You may not hear many innovators quote this directly to you. But you may have heard its more marketing related cousin about "building better mousetraps". And you have almost certainly seen this belief playing out in the actions of innovators and entrepreneurs. It can be subtle, it often masquerades as a clear "vision" but it is a misguided belief that just because I build something, people will obviously come. However, the harsh reality is that the exact opposite is most often true. In fact, "no market need" is regularly cited as the number one reason for startup failure. To put it plainly, just because we build it, doesn't mean they will come.

Enter the MVP, the most valuable player to emerge from the lean startup process– the Minimum Viable Product. This term, along with build, measure learn cycles, and quotes about failing fast are now near ubiquitous. However, a decade in, most innovators we speak to don't know where and how to draw these lines. This it highlights a dilemma that many now face– the lean innovators dilemma.

Let's return back to our Field of Dreams quote. While it is certainly true that just because we build it doesn't mean they will come, it is equally as true that if you don't build it they can't come.

Here is the tension. Building something is assumed– it is the first step in the build, measure, learn cycle after all. So the question isn't if we build– but what to build, and when to build it, and how much do you build?

Put more simply, when is something so minimum it risks not being viable? Or when does a focus on an excellent viable prototype sacrifice it being "minimum". Walking the tight rope of minimum and viable is the new innovators dilemma and we will likely need more than a sketch of a skateboard and a car to keep these two in tension.

So here are 3 practically tips and tools that I often consider when balancing this question that are specifically aimed at answering the questions of what, when and how much to build.

1. What to Build: Get Real and In-the-Wild

While the phrase "Fake it till you make" it has more to do with imposter syndrome than innovation practices it shows up when talking to innovators and entrepreneurs talking about testing business ideas. I am all for testing early and often– that is kind of the point of this article after all– even before you have built anything. Landing pages, prototypes and pre-orders can often get the learnings or traction you need. But the focus on in-market experimentation isn't about being fake, but trying to get as real as possible, without needing a huge, expensive build.

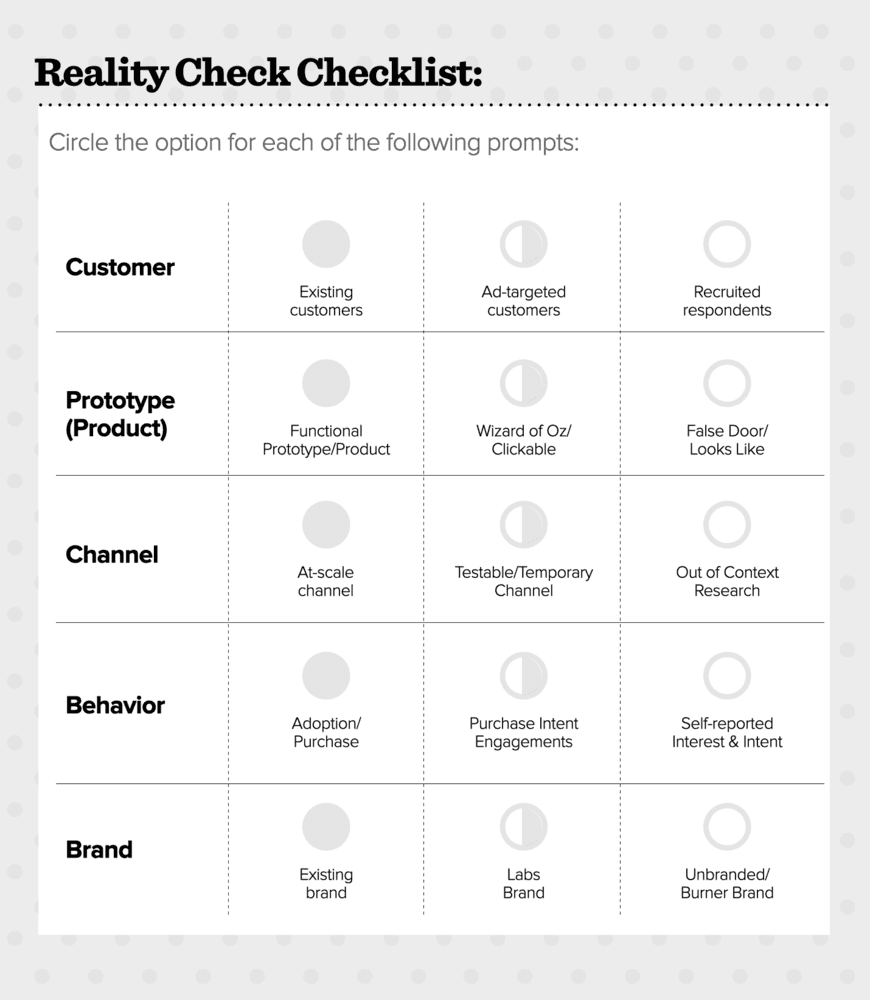

To aid in make these decisions while designing experiments I created a "Reality Check Checklist". This is a simple guide to identify what is most important to be truly real in regards to the customer, the product, the channel, their behavior and the brand. The simple litmus test is this, what is the most real version of an experiment that we can run in the next two-to-three weeks to test this idea?

One the far right of this checklist is a more traditional research practice, the far left is a fully functioning product/business sales mechanism. When building new ideas you will likely be all over the map and change throughout frequently throughout the process. This is a simple tool to identify specifically where you are on that journey. Which leads us to our next point.

2. When to Build It: Often

It may seem counterintuitive, but the goal of "sprints", being "lean" and "agile" practices aren't primarily about being fast. It is easy to believe that these practices prioritize speed for the sake of the speed– but that is simply not the case. The goal isn't to figure out how quickly we can design and deploy but rather to maximize the number of times you can get through the loop of building, measuring the outcomes and synthesizing into actionable learnings.

The more times you can complete the build, measure learn cycle the better. Done properly, each iteration gets better and better. The goal is to get through the cycle as many time as necessary to have clarity and conviction in the product/experience. Speed is just a means to increase the number, not the goal.

So with all of that being said, the answer to when to build is less about a specific time in the process, or a duration for a deliverable and more about the number of reps you can get. The answer is simply, often.

I am increasingly of the belief that one of the biggest advantages an innovation team, specifically a corporate innovation team, can give themselves is to have and own channels that allow for direct customer interaction. Be it a dedicated "Labs brand" that can quickly build and test new ideas, social media groups where new ideas are floated and tested for feedback, or even email lists that are built from day 1 of an initiative. Building and engaging a community of co-creators might be one of the best keep secrets of successful innovators for the next decade.

3. How Much to Build: Inform the Next Iteration

I recently read a quote by Garret Spiegel, the founder of Equalize Health that does a better job of summarizing this point than I could ever hope to do. He says:

"In design, everything is information for the next iteration"

The question of "how much" is arguable the core tension of the lean innovators dilemma, especially when working with creatives. However, one of the greatest secret weapons I have found is focusing on the next iteration. 11th hour requests, last minute builds, or impending scope creep is most easily addressed by saying, "Lets take a look at that in the next iteration" and refocusing on the specific goal to learn or deploy in the moment. This is a very natural conclusion– if– you are truly living out the first two principles listed above.

So the advice is simply this, keep your focus on the next iteration. Yes, have a big bold ambition and a clear and compelling product vision. However, you also need to see the many steps and iterations it takes to get there. Focusing on the next iteration does three key things.

Keeps your momentum forward. By assuming there will be a next iteration you keep forward momentum and take a posture that builds and builds often.

Takes the pressure off the version in front of you. This mindset also releases you from the burden to deliver everything to perfection in the moment.

Focuses your attention on what you need to learn. Finally, by considering the next iteration you focus on the immediate things that stand between you and what will come next and, most importantly, what we can learn to overcome them.

It is easy to fall prey to an all or nothing belief. Something like, "Without the full set of features the idea is just a shell of itself". This might be true, but more likely to be true is that there isn't a meaningful enough core problem and product to support a business. If your idea needs a bunch of bells and whistles to work you likely haven't defined your idea in simple and clear enough terms.

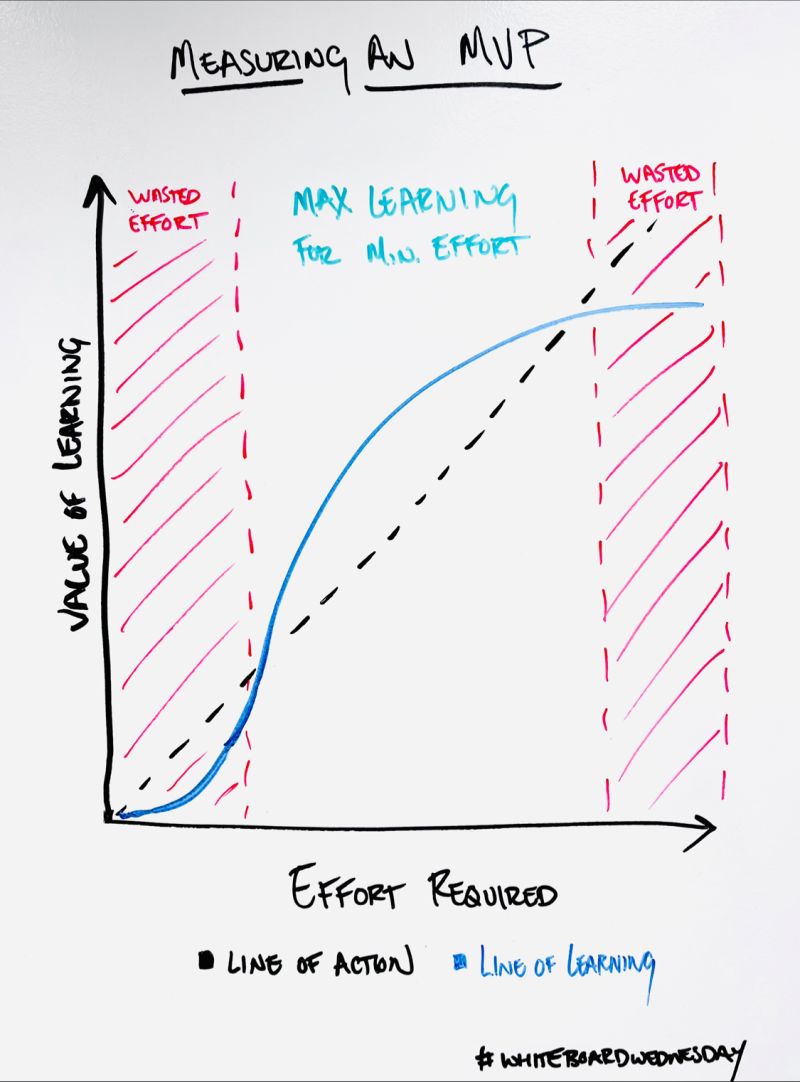

So how do you know when enough is enough? There is no silver bullet to give you the answer. But if we remember the MVP was originally defined by Eric Reis as, "the set of features in a product that offers maximum amount of learning with the least effort." However, in my experience the line of learning looks more like an S-curve than a straight line– as depicted in the whiteboard sketch below.

Practically what that means is that there is a point on either end where the effort required isn't worth the value of learning in return. While there is no clear formula to chart where you are on this curve you can use this framework to ensure you building and testing MVPs that are providing the maximum learning for the minimum effort required.

Conclusion: Build in Tension

I often say that innovators require holding two things in tension. The first is a relentless optimism to believe that something is possible. The second is a healthy skepticism that knows most ideas, especially in their first form, will fail. Embracing these two realities can make you feel a little crazy at times. It requires seeing the full potential of an idea, knowing just how hard it will be to bring it to fruition, but doing it anyway. The reality is this dilemma isn't new. It has always existed. And we have more tools and processes at our disposal to manage and mitigate it than ever before. But no matter how hard you try there is one thing that must remain true, you must start by building something because after all, if you don't built it, they can't come.